Friday, September 21, 2012

Not all opposite-color bishop endings are drawn

Boris Gelfand just won a textbook ending against Hikaru Nakamura in the first round of the Grand Prix event in London:

On the queenside, Black's bishop and two pawns paralyze White's four pawns with a dark square blockade. On the kingside, Black's two connected passers are mobile, and the Black king, bishop, and pawns coordinate with each other.. (Nakamura was even up a meaningless pawn for several moves.) So the final position is an easy win, even for you and me. Opposite-color bishop endings are funny that way: you can be two pawns up and it's a dead draw, or material is equal and somebody's completely winning.I should add that I followed this game live from the new website of The Week in Chess.

P.S. Alejandro Ramirez annotates this game on ChessBase.

Chess Life Online covered yesterday's opening ceremonies.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Anand's Accenture talk: decision-making

If you want to know how a World Champion makes decisions, prepares for play, uses the computer, and balances reason with emotion, then you should carve out 44 minutes to watch this low-key lecture.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

An "Anti-Sicilian" Trap

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.c3 is an "anti-Sicilian" line that might be called an "Alapin Variation Deferred." White prepares to grab the center with d4, and meets the natural 3...Nf6 with 4.Be2, when 4...Nxe4? 5.Qa4+ is a transparent trap. Best may be 4...Nbd7!?, forcing White to do something about his hanging e-pawn. The natural 4...Nc6, as in the game below, is playable, but allows 5.d4!? Black can then win material with 5...cxd4 6.cxd4 Nxe4!? 7.d5 (the point, meeting 7...Nb8? with 8.Qa4+, winning the knight) Qa5+ 8.Nc3 Nxc3 9.bxc3 Ne5 10.Nxe5 Qxc3+!? (the less greedy 9...dxe5 is possible) 11.Bd2 Qxe5 12.O-O! Qxd5 13.Rb1! and White has very dangerous compensation for his three(!) sacrificed pawns. In Basman-Stean, Hastings 1973/74, among other games, Black came to a grisly end. See Informant 17/439 or Shamkovich's book The Modern Chess Sacrifice for more details. Hodgson managed to survive after 13...f6!? in Gildardo Garcia-Hodgson, World Open 2000, as I also did in an Internet blitz game.

Black's 5...Nxe4??, as my opponent played in the game below, is just another way to blunder a piece, losing to the simple 6.d5. In Acunzo-Semenyuk, European Senior Championship 2011, Black soldiered on with 6...Nb8 7.Qa4+ Bd7 8.Qxe4, even managing to draw after White later hung a rook.

My opponent chose to lose a piece in a different way with 6...Nxf2, but I wrapped up the game in energetic fashion. Note that after 10.Bf6!, 10...gxf6? would have allowed 11.Bb5! double check and mate, à la Nimzowitsch-NN, Pernau 1910, which Bill alluded to the other day (position 14).

King and Pawn vs. King (Chess Homeschool, Day 6)

If we can't play positions with three pieces reasonably well, what hope is there for us with thirty-two pieces on the board?

I'm not providing solutions to any of the positions below yet: get Mom or Grandpa to play the other side and see whether the two of you can figure this out together.

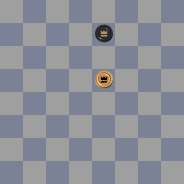

Usually, you want it to be your turn to move. Here, neither player wants to be on move! (Nerd alert: the technical term is reciprocal zugzwang.) When both kings can make it to the pawn's queening square, each player is trying to trick the other into a position like the one above.

In one-on-one basketball, what does the player with the ball do when the defender is in perfect position? Maybe a head fake: the attacker wants the defender to move in one direction so she can drive the lane in the other direction. The pawn's queening square (d8 in Position 4) is like the basket, and the Black king on d7 is a perfectly-placed defender: that's why Black doesn't want to move first! 1...Kc7 2.Ke6 or 1...Ke7 2.Kc6.

To understand Black's drawing technique with White to move, see Vince Hart's blog post, Straight Back Draws. Compare Position 4 to Position 2: Position 2 is always lost because the Black King has no room to go straight back! Of course, it's important to go straight back at the right time: 1.Kc5 Kd8?? loses because White can get to Position 2, but 1.Kc5 Kc7 2.d5 Kd7 and then....

The rook pawn is a special case. Either king can be stalemated on the rook pawn's queening square:

I'm not providing solutions to any of the positions below yet: get Mom or Grandpa to play the other side and see whether the two of you can figure this out together.

|

| 1) White to play draws, Black to play loses |

*******

|

| 2) White wins, no matter whose move it is |

|

| 3) White to play wins, but watch out for stalemate! |

|

| 4) White to play draws, Black to play loses |

In one-on-one basketball, what does the player with the ball do when the defender is in perfect position? Maybe a head fake: the attacker wants the defender to move in one direction so she can drive the lane in the other direction. The pawn's queening square (d8 in Position 4) is like the basket, and the Black king on d7 is a perfectly-placed defender: that's why Black doesn't want to move first! 1...Kc7 2.Ke6 or 1...Ke7 2.Kc6.

To understand Black's drawing technique with White to move, see Vince Hart's blog post, Straight Back Draws. Compare Position 4 to Position 2: Position 2 is always lost because the Black King has no room to go straight back! Of course, it's important to go straight back at the right time: 1.Kc5 Kd8?? loses because White can get to Position 2, but 1.Kc5 Kc7 2.d5 Kd7 and then....

|

| 5) White wins, either player to move |

|

| 6) Rook pawns are weird: draw with either player to move |

|

| 7) Rook pawns are very weird: Black to play draws |

|

| 8) White to play wins, Black to play draws |

|

| 9) A tricky square to draw! |

| |

| 10) White to play wins (in chess, the shortest distance between two squares is not necessarily a straight line!) |

| |

| 11) Black to play draws (Gligoric-Fischer, Candidates 1959) |

|

| 12) White to play: what happens? Black to play: ditto? |

There's much more to know: the Wikipedia article on king and pawn vs. king is a good place to continue. (Check out the 1908 study by Jan Drtina in the "Any key square by any route" section.) If you enjoy these endings, I can't recommend Müller & Lamprecht's Secrets of Pawn Endings strongly enough: it's amazing that these seemingly simple positions are so complicated and so beautiful.

Experienced players will note that I avoided the "O word"! I like to teach that by starting with a position from checkers:

|

| Black to play loses; White to play draws |

Monday, September 17, 2012

Queen vs. Pawn (Chess Homeschool, Day 5)

You already know how to mate with king and rook against king or king and queen against king. King and pawn against king is surprisingly complicated: we'll do that tomorrow. For now, let's look at major battles between king and piece vs. king and pawn. We'll start with queen vs. pawn.

In Diagram 1 above, Black is about to make a queen, and king + queen vs. king + queen is usually a dead draw. (We'll see some exceptions shortly!) So White must stop the pawn from queening.

When the pawn on the seventh is a knight pawn or a center pawn, the win is easy. Use queen checks to approach the pawn in a zigzag fashion. If the king steps away from the pawn, you can attack the pawn along the file, preventing it from queening, and make the king come back. Eventually, you'll force the Black king to step in front of the pawn on b1. Bring your king one step closer. Lather, rinse, repeat! It may take twenty moves or so, but White eventually win the pawn with king and queen and checkmate.

The above technique works great with center pawns and knight pawns, but it breaks down with rook pawns. In Diagram 2, the White queen will eventually make it to (say) g4, giving check to the Black king on g2. Black will play ...Kh1! White doesn't have time to bring her king up, as the stalemate must be released. So it's a draw with best play.

Diagram 3 is a draw, too. Imagine that White zigzags to (say) g3, giving check to a Black king on g1. Black sacrifices the pawn with ...Kh1! and White can't make progress: the reply Qxf2 is stalemate. Get out the pieces and try this yourself!

Diagram 4 (taken from Müller and Lamprecht's Fundamental Chess Endings, position 9.03) is a very cool exception: if the king is close enough, you might be able to find a way to let Black make a queen, then catch Black in a mating net! (Visualize the position: White Kb3, Qd2, Black Kb1, Qa1: even if it's Black's move, is there any way for Black to escape this predicament?)

In Diagram 5, White can again allow Black to queen, then deliver mate on the c2 square. |

| 1) White to play and win |

When the pawn on the seventh is a knight pawn or a center pawn, the win is easy. Use queen checks to approach the pawn in a zigzag fashion. If the king steps away from the pawn, you can attack the pawn along the file, preventing it from queening, and make the king come back. Eventually, you'll force the Black king to step in front of the pawn on b1. Bring your king one step closer. Lather, rinse, repeat! It may take twenty moves or so, but White eventually win the pawn with king and queen and checkmate.

|

| 2) White to play: Black draws |

|

| 3) White to play: Black draws |

|

| 4) White to play and win |

|

| 5) White to play and win |

| ||

| 6) Angelo Young - Awonder Liang, Skokie 2012: White to play and win |

There is no substitute for trying to work these positions out for yourself: that's the way you'll remember them! Answers later: let us know if you get stuck.

Silman's Complete Endgame Course is a great reference for young players. It's available as an interactive app for the iPad.

Sunday, September 16, 2012

It's a metaphor

No Harry Potter, no Kronsteen, no Knight playing Death, but 101 checkmates in film.

Of the actors pictured, Bogart was one of the strongest chess players in real life. (Peter Falk, who didn't make the cut, was no patzer, either.)

Parental advisory: at least two instances of profanity and one (bloodless) murder.

Via ChessVibes.

Of the actors pictured, Bogart was one of the strongest chess players in real life. (Peter Falk, who didn't make the cut, was no patzer, either.)

Parental advisory: at least two instances of profanity and one (bloodless) murder.

Via ChessVibes.

The Greatest Game You've Never Seen

This is an amazing game by IM Nadanian, featuring his patented 5.Na4!? against the Grünfeld. The diagram shows the position before all hell breaks lose. The final position looks like a composition: despite Black's huge material advantage and all those pieces clustered around his king, he has no defense against the primitive threat of 18.Qh8#. Astonishing. This game deserves to be in all the anthologies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)